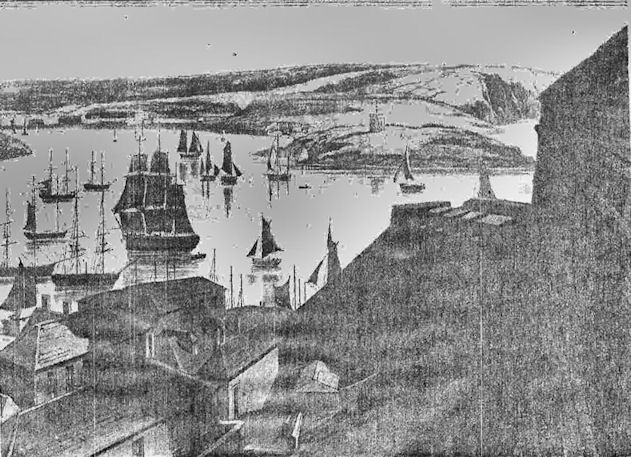

The Emigration Depot.

In the 1840’s the emigration was to the United States because the passage was the cheapest and opportunities apparently greater. To siphon some of this flow into the more distant colonies the government created the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners in 1840, acting as agents for the colonial governments who sold land and used the proceeds to assist passages to the Cape, Australia and New Zealand. Depots were set up by private contractors at Deptford and Plymouth, in the vacated Victualling Yard premises at Lambhay. The building run from the Barbican gateway to Fisher’s Nose where the emigrants waited for the chartered ships.

The Victualling Yard was originally built by a man called Rattenbury in 1654. It was used for many things, then in 1705 it was once more a Victualling Yard. It burnt down in 1744 destroying many stores but was rebuilt and enlarged the next year. After the Napoleonic Wars the stores were moved to the newly built Royal William Victualling Yard at Stonehouse.

In 1845 the Lambhay Yard was owned by the Ordnance Board but in the occupation of Thomas Gill. In 1847 the storehouses at Elphinstone Wharf, between Phoenix Wharf and Fisher’s Nose, was made into a Government Emigration Depot.

The Depot at Elphinstone housed the poor, those driven from Ireland or the western counties by poverty and depression, who were being given assisted passages. The Government Emigration Agent in 1852 was Lieut. Carew, R.N., and he told a health inquiry that the depot, capable of holding 500 emigrants, was supported by the Colonial Land Funds in Australia. Only those with an emigration order were admitted, and a vast number came from Ireland. It was in a healthy part of the town, was spacious, well-ventilated, and had no cesspools. There had been no deaths in the cholera outbreak of a year or two earlier, and in his five years there only twenty-five people had died, and those from wounds or infections caught in journeying to the depot. Those who arrived sick were placed in isolation, and in his view there would have been more disease, and much distress, without the depot in which the people could await their ships. The ladies of the town, he reported, gave time and money to help the people.

One can see how the poor made up the mass of emigrants from the figures; in 1859 for instance there were 338 cabin class emigrants as against 3,786 going steerage. Most that year are shown going to the “East Indies”, with New South Wales, Victoria, and the Cape of Good Hope also taking over 500 people each. Health conditions at the depot were falling, however, probably due to people coming from homes already long hit by poverty and their resistance to disease weakened by malnutrition. A report to Plymouth Public Dispensary in January 1860 showed that of 102 children who had died of measles in the town, 32 had been taken from the Emigration Depot. In October and November 47 people had died there, out of a total of 412 souls, a death rate of 114 per thousand compared with 6•38 for all Plymouth and a heavier mortality even than that of King Street West, a large and densely crowded district.

But the flow went on. In 1876 over 10,000 people sailed in 25 ships, and in 1878 there were 15,500 in 100 ships, with a record exodus of 1,800 in a week. At that time, apart from a civilian Government emigration officer whose job under the current legislation was to see that the ships and the rations were adequate, there were agents for New South Wales, South Australia, and New Zealand.

In 1883 a Mr. Arthur Hill of Reading had the job of running the Emigration Depot. He completed a scheme of improvements and extensions (even adding separate lavatories) which gave 1,118 fixed berths, 372 for single men, 402 for single women and 344 for married couples and children. There were five large mess rooms, and it was described as “the only establishment of its kind on any considerable extent in the country.” By the time assisted passages ended around the turn of the century between 300,000 and 400,000 emigrants had sailed from Plymouth. In the government eyes it was the right site, Plymouth, because it was convenient for the Irish, and more emigrants came from Devon and Cornwall than any other English counties – a comment on the rural economy of the West Country.

Plymouth became the Australian mail port in 1852 and soon all the great British companies, Union, Royal Mail, Peninsula & Orient, instituted regular Plymouth calls. But it remained a port of call; Southampton or the London river were the base ports and Liverpool the Atlantic port. As time became important and the liners grew in size so they began to anchor inside the Breakwater and tenders went out to embark or land mail and passengers. At first these steamers were hired but in 1873 the ‘Sir Francis Drake’ was specially built for the service, and in 1876 the ‘Sir Walter Raleigh’. A fleet of four or five tenders, all named after Plymouth Elizabethan sea captains, were in service from 1890.

In 1869 special travelling post office sorting vans were attached to the trains carrying ocean mail from Plymouth but passengers still had to take cabs to Millbay station. In 1882, P & O then in 1883, the New Zealand Shipping Co., increased their use of the port, dockside facilities were much improved the ocean mail trains were introduced which passengers joined on the dock.

From 1907 onwards about 500 liners called at Plymouth every year. The majority of calls and passengers were inward bound, for with the ocean mail trains a day or more could be saved in reaching London, as against steaming up-Channel to Southampton.

In 1879 3,538 passengers passed through Millbay, by 1889 10,418 by 1907 21,181 and in 1913 30,841. Mailbags handled reached a peak of 219,691 in 1913.